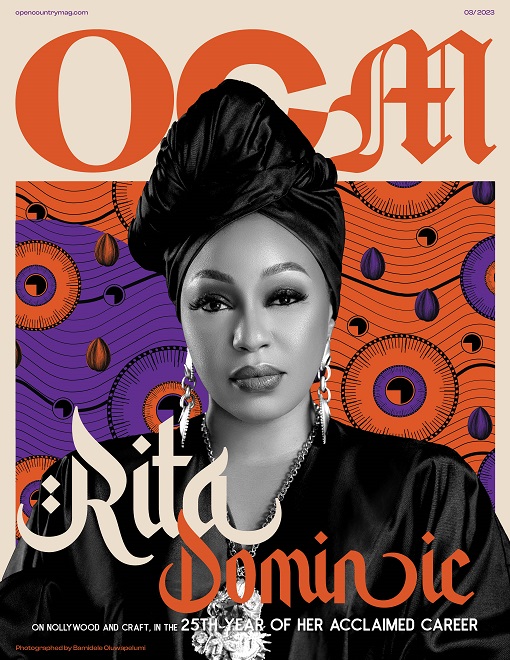

During the final days of post-production for The Meeting, the 2012 comedy that helped set a new quality standard in Nollywood, the director Mildred Okwo had a problem. She and her team had shot a key scene over and over, but in the editing, she found that they’d missed a detail. In the final cut, the female lead character Clara Ikemba, played by Rita Dominic, is greeting an oba who has just arrived at the office of The Honourable Minister, where she is the receptionist. She is kneeling on the floor before the traditional ruler, almost praising him with her hands. In the sequence that missed making it into the film, Dominic is not just kneeling but hunching even lower, wiping the floor with not only her hands but her hair.

Clara Ikemba is no ordinary receptionist. By deciding who gets to see The Minister and who doesn’t, all based on her mood swings, she is a power broker. To the roomful of Nigerians complaining and waiting on her whims, she is the tin deity that must be placated. Yet when the oba enters, she falls on her knees in delight, an act of complete subservience, and the people in the reception gape at her in shock. Power is a game that informed Nigerians play at the right time, with the right person, and this is Abuja, the country’s capital, where everyone knows who is who, especially people like Clara whose power are fickle in principle but terrifying in practice.

Dominic cleaning the floor with her hair was a minor detail but the kind of deep delve into character that viewers were not accustomed to seeing onscreen in Nollywood. And they would have seen it had it not been for cameras that were focused higher and did not move with the actor.

“I should have done a cut out of her doing that but I felt it wouldn’t have been as spontaneous,” Okwo told me. “That was a lesson I learned, because the more takes we took the more she got into character. It was instinctual for her. She’s so good at giving you almost the same thing every single take, with the same emotion, and you can edit her easily because she doesn’t mess up the continuity. For me, that’s one of the ways of knowing people who really understand what acting means.”

At the time The Meeting premiered, Dominic was already one of the industry’s superstars, with almost 15 years of work. But back then, in 2012, when the idea of New Nollywood, with its better cinematography, was only taking root — with support from then president Goodluck Jonathan, who ironically endorsed the film — not many viewers would have cared much if any actor had been subpar in such a scene. These days, though, with a sharper audience no longer willing to substitute storytelling for flashy photography, most subpar acting would be roasted on social media. What it also means is that people increasingly revisit standout performances in new appreciation. Last May, for example, there were tweets praising Dominic in The Meeting as “one of the best Nollywood performances ever.”

There are people who delight in frustrating other people and then there are devils you cannot bargain with. Clara, with her makeup-wrinkled face, is the latter. She delivers side eyes to the people waiting, she reschedules their appointments without telling them, she gets security to throw them out when they protest too much, all the while chewing gum with alacrity. She lets The Minister’s mistress, played by Nse Ikpe-Etim, into his office, to the chagrin of waiting visitors, whom she then invites to buy the soft drinks and recharge cards she sells, while still ignoring their efforts to use purchases as bribes. Even though she is Igbo, even though it is a country where ethnicity is often a ticket to political access, she mistreats everyone of every ethnicity equally — her allegiance is solely to class. But even as Clara makes you laugh, Dominic doesn’t let you forget that this kind of frustration is real, that the doors of government offices are often where dreams are dashed.

Clara’s reception room is only one half of the plot of The Meeting. In fact, Femi Jacobs’ Makinde Esho, the businessman whose efforts to secure the titular meeting are frustrated by her, is the one through whose eyes we see the story, and he has more screen time, and even a romantic storyline on the side. And yet you come away thinking of Clara, and of how Dominic delivers most of her performance from the compact space of a receptionist’s table area, while seated.

“While we were filming, there wasn’t a moment that Rita dropped the ball on her character,” her co-star Nse Ikpe-Etim told me. “She delivered. Stellar.”

When the film was first released in 2012, playing 14 cinemas and grossing over N25 million (and later selling 50,000 copies within two weeks of DVD release in 2014), many viewers could tell: a new benchmark had been set for acting in Nollywood.

Almost 30 years have passed since Nollywood became an international phenomenon with the 1992 release of the Igbo-language film Living in Bondage. From the ‘90s until the mid-2000s rise of Afropop, Nollywood reigned as Nigeria’s biggest cultural export, converting a national audience used to Hollywood and Bollywood films and minting superstars: Liz Benson, Genevieve Nnaji, Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde, Pete Edochie, Nkem Owoh, Stella Damasus, and Saint Obi, among others. The actors’ profiles grew astronomically, displacing footballers at the top of the country’s pop culture hierarchy, permeating conversations in everyday life. But unlike in Hollywood and Bollywood, the growing industry’s faces were women, who became its brightest stars and highest earners. For most younger millennials like myself, there were few greater joys or scares than returning from school to watch Nkiru Sylvanus weeping in A Cry for Help, or Patience Ozokwor as an evil stepmother in every role, or Osita Iheme and Chinedu Ikediezie as the tricky Aki and Paw Paw.

Most of the flicks were slapstick comedies or tear-jerking grass-to-grace stories or occultic frights, with enough entertainment, and overt moralization, but not enough artistic intent. The acting talent was obvious but the craft was not. The romances were powered by familiar pairings: Genevieve Nnaji and Ramsey Nouah, Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde and Desmond Elliott, Kate Henshaw-Nuttal and Emeka Ike, and for Dominic, it was often with Jim Iyke, typecast as the bad boy to her good girl.

Then, in 2004, the industry decided to ban its eight highest paid stars for charging high fees. The curious decision puzzled the public, but it gave space for a new set of actors who now had enough visibility to rise into superstardom, including Mercy Johnson, Chioma Chukwuka, and Dominic.

Dominic’s first role to receive acclaim was in 2007’s White Waters, a drama by Izu Ojukwu, but it was in the following decade that she reached a new level all her own. Across defining roles — as a self-destructive Kenyan woman reeling from a traumatic childhood in 2011’s Shattered, as the hilarious Clara in The Meeting, as the worried wife of a soldier accused of coup-plotting in 2016’s ’76, as a mother who survives sexual assault in 2019’s Light in the Dark, as a singer and classic femme fatale in 2021’s La Femme Anjola — she morphed into very different characters and displayed some of the best acting in Nigerian film, blending skill and experience into a modulated range rarely seen in the industry.

For all five performances, she was nominated for the Africa Movie Academy Award (AMAAs) for Best Actress in a Leading Role, winning on her first attempt for Shattered. She is the most nominated actress in the AMAAs’ 18-year history (and the second-most nominated performer overall, tied with the Nigerian actor O.C. Ukeje on five, both trailing the Ghanaian actor Majid Michel, who notched six, five in lead, like Dominic, and one in supporting). At the industry’s other major awards show, the Africa Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards (AMVCAs), she jointly holds the same record with five nominations (tied with Funke Akindele). There, she is the only person to win Best Actress in the two categories, in Drama for ’76, in 2017, and in Comedy for The Meeting, in 2015, a year in which she was also nominated in Drama for Frank Rajah Arase’s ancient Benin Kingdom epic Iyore.

As impressive as her range is her longevity. She is the rare Old Nollywood star whose work now leads the way in the New Nollywood era. It is a singular career that has allowed her to retain, for over a decade, the trifecta of actorly relevance: the adoration of viewers, the acclaim of critics, and the admiration of peers.

In 2012, a blogger cited her yearlong output and concluded: “She has booked her place solidly as one of the best Nigerian actresses – of all time.” The assertion may have registered as hyperbolic then, or may not have registered at all, but, in a developing industry with developing media that does not always track granular changes, distinctions seemingly only emerge in casually sampled opinions. Sometime ago, quoting one of those Tweets asking people to generate controversy, I’d called her “the best actor the industry has to offer,” expecting pushback or reluctance. None came. The culture critic Jerry Chiemeke wrote: “Is it even a debate? She’s one of only 6 Oscar-worthy actors that Nollywood has got.” A response that then enticed debate, with commenters asking: So who are the other five?

Dominic spoke to me for this cover story almost two years ago, in April of 2021, four months after Open Country Mag launched. It was a fine Tuesday, and it was a video call, and she was in an airport, pulling along a box until she found space to sit. She lowered her nose mask. “I’m sorry, I am in transit,” she smiled through her glasses. “How are you?”

A part of me worried that people might see her and swamp her and our interview would be over. It’s not only because she’s a huge star in a public place; it’s also because she belongs to that small cadre of celebrities whom the public seem to unreservedly adore because they carry themselves with grace and remain unstained by scandal.

She has always been in the public eye, from when she was a child. Her full name, Rita Uchenna Nkem Dominic Nwaturuocha, says a bit: she is from the royal Nwaturuocha family of Aboh Mbaise. Her father was a medical doctor and her mother was a nursing officer and she was the youngest of four children. It was a full house: cousins, family friends, relatives.

“My mother always said that, as a baby, I watched everything on television, everything and anything, whether I understood it or not,” Dominic laughed. “She said that it was then that she knew that this girl had a calling.”

Every weekend, her mother prepared her for two children’s shows called Children’s Variety and Children’s Opinion. Her life was a triangle of school, playground, and presentations. She entered dance competitions and appeared in school plays. She liked music, and, in secondary school, she was vice president of both the Dramatic Club and the Press Club, and later became Social Prefect. Even as her parents encouraged her, she watched as her friends fell away, pressured by their own parents into studying “something worthwhile.”

In 1994, she arrived at the University of Port Harcourt to study Theatre Arts. “I started to watch more films and understand them,” she said. “Because it’s different when you’re a child, you don’t understand it as much. I watched a lot of foreign films.” She took a liking to Nigerian home video stars: Joke Silva, Taiwo Ajayi-Lycett, and Liz Benson. “These were the women I drew inspiration from. I felt, these women have done this; you could actually do this, you know, tell stories, create.”

In her year of graduation, 1998, she secured her first role, the female lead in a romantic comedy called My Guy, opposite comedian Ali Baba, whose character tries to hustle and adapt to Lagos life. Before that film came out in 1999, though, a later role she landed, in A Time to Kill, was released in 1998, and became her “first film.”

She remembered her first time on set as challenging. “When I studied Theatre Arts, they didn’t really teach us how to act in a film,” she explained. “Stage acting is different from film acting. On stage, it’s larger than life, you have to overdo it, basically. But film is, less is more. I struggled for years, you know, to learn how to act in film. I had to learn and make that transition by myself.”

For someone with a calming presence, Dominic finds herself playing toxic or traumatized women. It’s even more intriguing when you consider that Clara in The Meeting is the least wrecked of them all.

“I sometimes ask myself that question,” she laughed. “When I watch these films and see these women, I’m wondering, I don’t recognize myself any longer, who are these people?”

In embodying these women, she wears their wounds boldly, often with a signature phlegmatic disposition — a pattern that led a Twitter user to suggest that she is “Nollywood’s only real Method actor.” But I don’t think that what she does is Method acting. I suspect that her gift for internalization comes from elsewhere: empathy. Perhaps growing up in a household full of people gave her empathy, made her a better observer.

Take Keziah Njema, her character in Shattered, a film by the Kenyan actor Gilbert Lukalia, which came out before The Meeting. Keziah is based on a true story, about a middleclass Kenyan girl who was molested from age three by the men meant to protect her. The role was unlike the wives and girlfriends Dominic had played before, and it demanded from her — to be vulnerable, tormented, excitable, reckless, fearful, broken — it demanded from her until, in her own words, she “almost dropped.” On some days, she left the set crying, thinking of young women going through the same horror as Keziah.

Ahead of the release, then, she told Fab Magazine, “I had to go very deep to pull out some acting demons to play this character. By the time we were done, I had nothing else to give.” The AMAAs responded and gave her its Best Actress award — after bloggers already installed her as the frontrunner.

(In Kenya, however, her Best Actress win at the Kalasha Film and Television Awards was ill-received by some industry insiders. Tinsel actress Lizz Njagah reportedly said: “It is cynical to have a Nigerian actress nominated for the Best Actress category in Kenyan awards, thought the awards are meant to celebrate Kenyan talents, anyway I am not saying that Rita Dominic is not a good actress she is very good” [sic]. And, in the time-honoured tradition of Europeans assuming authority in Africa, Njagah’s husband, a Greek director named Alexandros Konstantaras, called the voters’ choice an “epic fail.” Only two years on, though, Njagah, in the midst of another industry controversy, reportedly tweeted that she was relocating to Nigeria.)

Keziah, the traumatized woman in Shattered, was unlike the wives and girlfriends that Dominic had mostly played at that point in her career.

Keziah, the traumatized woman in Shattered, was unlike the wives and girlfriends that Dominic had mostly played at that point in her career.

Keziah, the traumatized woman in Shattered, was unlike the wives and girlfriends that Dominic had mostly played at that point in her career.

For Dominic, a vision of character is the starting point. Where Keziah is a woman in need of protection from the world, Clara is a reality you hope to protect yourself from; it is a wide gulf between the thorny melancholy of the former and the choleric impunity of the latter, but she delivered both within a year. Where does she draw from to inhabit these women?

“Back stories help a lot,” she replied. “It’s not in the script but it’s like creating a little history for the character, a little biography, giving her a personality, who she is, where she’s coming from. What is her environment, how did she live, what happened to her as a child, why does she behave the way she behaves now, what informs her decisions?”

When she took the role in Shattered, a few eyebrows were raised in Nigeria: what did a big star like her see in a Kenyan production? But she needed it because, at that point in her career, she wanted to be seen as an experienced actor, as one who can handle, as she told YNaija, “inspiring stories that will touch people’s lives.” So she cut herself off from social circles, dug into research on drug addiction, looking for a way to translate the ecstasy and the withdrawal, how someone struggling might slash their wrist, until, finally, she herself began to “feel all the hurt and the mixed feelings the person whom I was playing went through.” And then, on top of these, she learned Swahili. But while she avoided her Nigerian accent, she could not do a strong East African one, so she settled for a polished Kenyan intonation. After her performance, she read Michael Caine’s Acting in Film.

What she looks out for is something with which to understand the character better. “It helps you interpret the role better,” she added. “These are things I do with the help of the director. Not all directors do that, but there are directors who understand what characterization means.”

The director Izu Ojukwu, who considers Dominic his first-choice actress, told me why he is drawn to her passion and creative temperament. He had been following her work since the early 2000s and found her relatable. But the first time he tried working with her, an executive producer in the middle of communication overplayed his hand and talks collapsed, which made Dominic look like one of her demanding characters. His second attempt worked, and he cast her in White Waters. The film is named after the English name for Farin Ruwa, a waterfall in Nasarawa State, where they shot it. It was a promising tourist attraction that was wasting away.

“Rita kept calling my people and asking, is the place like Obudu?” Ojukwu told me. “They just kept telling her yes. They drove into that location in the middle of the night — it’s way out of civilization — and the place turned out to not be what we expected. Rita was angry and said she was leaving the next day. I said, why don’t you just sleep and we will talk in the morning?”

When Dominic woke up the next morning and came outside, she was stunned at how beautiful the place was. It was as if the clouds were strolling across the windows. “I was watching her,” Ojukwu recalled. “Everything changed, the anger, the disappointment, all gave way. You know, I saw tears in her eyes. She just turned and hugged me, and I saw the Rita that I expected to see based on the performances on TV. She said now she understood why I brought them there.” She made a call to Lagos, postponing her engagements.

“I could tell what kind of passion drives her, it tells me a lot about who she really is,” Ojukwu said. “I’ve always said that she’s a consummate artist. The job comes before everything. She loves what she’s doing and her performance in that project was incredible. At first, we struggled to get each other, but with trust established, everything else fell into place.”

He continued. “She is my first choice because she takes her job seriously. Sometimes I tell people, it’s not about your performance in front of the camera, it’s how relatable you are outside the camera, you know. She hardly goes to a set where people don’t fall in love with her. You need a good working relationship with the cast and crew because they feed off each other. She is a very humble person, accessible, but, of course, you cannot also take her for granted, because, one moment you try to take advantage of her simplicity, she quickly draws the line.”

In 2013, Ojukwu sent Dominic the script for ’76, written by Emmanuel Okomanyi. The story, set six years after the Biafran War, in 1976, is about a young military officer who is accused of coup-plotting. Captain Dewa, an Edo man, is played by Ramsey Nouah; and Dominic is his pregnant wife, Susie, an Igbo woman, whose ethnic group was vanquished in the war. The cast — including Chidi Mokeme as Dewa’s antagonist Major Gomos — were in Ibadan for six months, rehearsing in the first two and shooting in the remaining four. They sat together and discussed the story, visualizing the characters.

Susie, as written in the script, was already a deep role, but Dominic approached it as much more — a chance to shake off industry efforts to typecast her as her comic character in The Meeting. Where Clara is a purely external performance, Susie required internality to go with the physicality. Dominic had learned over the years that character is an amalgam of script, costume, makeup, and set design, but she needed more for Susie: she wanted to reach a convincing emotional tipping point. For research, she scoured Web pages and YouTube clips.

“There was one of a Biafran woman during the war, an Igbo woman living in the north,” she told me. “I studied her a lot. She was just a regular person who was caught in one of those videos on the war and post-war times. I just watched her, what she must have been going through. I think she was married to someone in the north. She watched her father get killed. I could see her struggle. It was a short video, but from there I just started imagining what it must have been like for her, knowing what had happened to her father.”

The isolated set also helped. The story was filmed in the Ibadan barracks, and she used the chance to speak to wives of soldiers, listening to their stories. “Sometimes they just call their husbands off and that’s the last time they see them, you know. Their husbands go off to war, they don’t know if they will see them again, but they just have to stay strong for the children. Seeing these women gave me the strength to channel Sussie.”

Dominic decided to play the character from the inside and then proceed outwards, coming out of herself as the story progressed, as the fight picks up for the life of her husband and that of her unborn baby. Being pregnant meant that detailed physical movement was limited, and what she did was bring it all on her face. Watch that poignant scene when a midwife tells her, “The day wey you agree to marry a soldier, na dat day wey you don decide say you go sacrifice your life with am to serve his country.”

Watch her stilled face as Sussie sits dressed up on the balcony, waiting for her husband, and a soldier approaches on a bicycle, and more soldiers follow in a van, and, just as the cycling soldier reaches her compound, force him to follow them. Watch her tentatively stand, hand still on waist. Watch the later scene where she slowly turns as a soldier walks her and her baby away, watch her nod thank-you to her neighbour. It is flawless minimalist acting, her heavy internal conflict manifesting in tiny external details, like the wringing of hands or too-open eyes.

After the coup fails, she becomes a woman whose very words, her yes or no, her ability to remember which was justified, could sign her husband’s death warrant. And she chooses her words, pushing back against intimidation, threatening a corporal, wearing her face like an armour. When her husband is arrested, a soldier driving her tells her to come down from the car and she says, “Not until I see my husband.” With steely determination, she tells another, “Captain, I think you are adopting another approach. Why don’t you try another method? Perhaps, that might work.”

’76 came out in 2016. Ojukwu’s pairing of Dominic and Nouah was inspired, almost a corrective to Nollywood’s traditional romantic pairings of glamourous actors having garish heartbreak. It helped that Nouah, a talent on equal footing with Dominic, turned in his most memorable work since The Figurine. Yet there is something independently alive about Dominic’s Susie, the character’s ability to charge out of her usually quiet self. Some consider it to be her finest work. I consider it to be the most complete performance by a Nollywood actor, female or male, for as far as my memory can stretch.

When Dominic spoke to me from the airport, she was in the midst of promoting her film La Femme Anjola, in which her titular character, Anjola, is a talented singer and bewitching lover. The neo-noir film, directed by Okwo, had arrived in a slightly different cinema culture. The films that dominated were mostly romantic or action flicks, or glitzy portrayals of affluence, or exaggerated comedies that play like long Instagram skits and are stuffed with social media personalities and targeted at their millions of followers. The few serious features that matched them in popularity were stacked with big names, as with Lionheart and King of Boys, or were sequels, as with Living in Bondage: Breaking Free. And then came La Femme Anjola: a serious, anticipated film that mixed genres, whose hopes rested on a single marquee name in an era when most traditional stars no longer had the pull they once did. The film site Sodas ‘n’ Popcorn ran a post titled “Are We About to Test Rita Dominic’s Box-Office Might?”

The release did not go smoothly. The Cinema Exhibitors Association of Nigeria (CEAN) reported first-week figures of N8.1 million from 49 cinemas, which Okwo questioned on Twitter. Then a week later, with its total at N13 million, FilmHouse pulled it from most of their screens, leaving it only in four locations even though it was the No. 2 film in the country. Okwo pointed out that FilmHouse had also pulled her previous film Surulere in its second week, even though it was the No. 1 Nollywood film in the country. It set off a reaction on Twitter, with fans spotting a pattern: FilmHouse had also pulled Nigeria’s first-ever Oscars submission Lionheart, prompting public criticism from its star and producer Genevieve Nnaji. YNaija cited the La Femme Anjola development as another reason why Nollywood needed more cinemas — a gap that had been highlighted years before by the National Film and Video Censors Board (NFVCB). The result was that a vast number of filmgoers were robbed of a chance to see it.

At a time when the few serious films at the box office were stacked with big names or were sequels, La Femme Anjola relied on Dominic’s star power for its odds.

At a time when the few serious films at the box office were stacked with big names or were sequels, La Femme Anjola relied on Dominic’s star power for its odds.

A heady mix of romance, thriller, and character study, La Femme Anjola Africanizes old Hollywood tropes. Here, Dominic is in her seductive element, and her victim, Dejare, played by singer Nonso Bassey in a blistering film debut, can only ward off what she shows him. Her Anjola is unknowable: a woman who parlayed her sexuality and talent into a man’s good graces, and, now assimilated into a higher social class, projects a large personality with a tiny hole. Bassey’s Dejare thinks the hole is vulnerability and gets sucked in.

Someone told Okwo that Anjola’s manner of speech sounded fake, and Okwo laughed. “That is the point! We don’t really know who Anjola is. When I was having meetings with Rita, we figured that Anjola just totally built a persona for the benefit of being part of a certain class in society. She lies, so we don’t really know how much to believe about her background. Rita played her like a lot of these wannabes in Lagos, where you don’t have very good education but you want to sound like you do, but you really are not pulling it off. It was also to deceive Dejare, who is an aje butter. I’ve always felt that you only saw the true Anjola maybe two or three times, and Rita truly understood her.”

The men in Anjola’s life should have. In the film’s violent central scene, she is so methodical, you wonder how many times she has done that before. In his review, the writer Kanyinsola Olorunnisola sums up her behaviour in the scene as “victim, vanquished, victor.” And when she looks up moments later, it’s almost as if she is asking the viewer: Have I done enough now? Have I?

Nigerians have a fascination with the Old Nollywood generation that we may never see again, which perhaps came from having watched them for so long on our screens, in the privacy of our homes, that some of us wanted a piece of their actual life. This interest is concentrated on the star actresses, some of whose personal lives played out in gossip blogs, and the more glamourous they were, the juicier the stories.

For years, Dominic’s romantic life was fertile grounds for speculation. Two years ago, in December of 2020, she ended it by sharing photos with her man, Fidelis Anosike, a media entrepreneur and owner of Daily Times and Miss Nigeria. (Disclosure: I used to be an employee of Mr. Anosike’s.) In April of last year, she married him in a lavish traditional wedding that drew some of the industry’s biggest stars and was the most talked-about Nollywood wedding since Banky W and Adesua Etomi’s in 2017.

As with every celebrity culture, the public’s love is often conditional on the person’s image, and so Dominic marrying at 47 spawned social media hot takes and YouTube videos, about how she “maintained her role model status” and focused on her work and was “patient until she was ready.” And yet, in a world where success and fulfilment are perceived as not happening unless they were rushed, there is value, at least for those content creators and their followers, in seeing that the only timeline and life goals that matter are those they set for themselves.

The question of image is one that has plagued Nollywood stars long before “branding” became a buzzword. Many top actresses took only roles that amplified their public image: where some willingly typecast themselves, others restrained themselves from exploring the character if it required them to look a way they didn’t like. The Meeting was striking partly because Dominic ditched the glamour. While it is the sensible thing to follow the art, it could easily have been detrimental to go against convention. Did it bother her?

“No,” she shook her head. “That’s the thing. I keep telling up-and-coming actors, leave the glamour for when it has to be you. When you’re playing a role that requires you to be a certain way, be that. Don’t be scared. It’s important to separate them, otherwise it will not be believable.”

That was not to say that she had no reservations about becoming Clara. “When it came up, I didn’t even want to play that role, to be honest,” she said. “That was the first time I was producing, and having to play this difficult, intense role — but Mildred convinced me, somehow. But in terms of thinking that it will affect how people see me, affect my image and presentation and all that, no. And that’s what I like, playing such roles that, when I’m watching them, I don’t see myself. Because I learn from these characters. I go on a journey with them. I live lives through the characters.”

She told me that, after The Meeting, directors sent her more comedy scripts, with funny, razz roles, and she turned them down. That same year, she appeared in Streets of Calabar, a comedy-thriller by Charles Aniagolu, where she crossed genders to play both a woman and a man. She isolated herself on the set, because if she interacted with people, she would do so as a woman, which would take her out of the male headspace. Her exactitude comes from watching the greats: Audrey Hepburn, Meryl Streep, and Cate Blanchett (whom she might have watched play a man, Bob Dylan, in I’m Not There).

Each role taught Dominic something, she said, because they are all different. But it was ’76 that changed what she thought she knew. “Let me tell you something,” she leaned forward into her phone’s camera, “for me, in ’76, I never — you begin to understand that the unsung heroes are the wives. It made me start studying, because they didn’t really teach us about the war. It made me start looking for info on the ‘70s.”

In an industry still in development, it is sometimes easy to see when an actor has pulled ahead. It is difficult to think of anyone else, in the last 13 years, who has put in as many strong performances as Dominic.

Ojukwu told me that The Meeting was, for him, the moment that Dominic stood out. “It was mind-blowing. It confirmed to me everything that I imagined about her. Sometimes you are good and you are not properly managed, and you fall into that stereotypical trap, and you keep doing the same thing over and over. But her ability to go from that elegant, sophisticated personality in some movies to bringing herself down to that partially educated, typical government clerk — everyone that I’ve spoken to, we talk about how she brought that character to life. She did not place herself above that character. Her ability to not bring her personality over the character makes her unique, and it’s stood her out amongst her peers.”

Nse Ikpe-Etim, who picked Dominic’s work in The Meeting and Shattered as her favourites because they show “her versatility and ability to get gritty,” told me that Dominic’s professionalism is greatly admired by her fellow actors. “Rita is the calm before and after the storm. Her personality makes you long for more. When all hell breaks loose, she holds your hand. That’s been my experience. I don’t think I’ve told her how much this means.”

Okwo credits Dominic’s preparation before getting on the set. “She doesn’t depend so much on her instincts anymore; she comes to set prepared, she knows what she wants to do, and, of course, if the actor she’s with does something different, she’s always ready to receive and to make changes. It’s very important because a lot of actors don’t come to set knowing what they want to do with the character; they don’t realize that, as the stakes get higher, you must match the energy of each scene. Rita is the kind of actor that, if she has a role in a week or so, she will stop communicating with people. Depending on how the role is, she would just stop going out, to give time to the character before she gets on set.”

Okwo added that such serious attention to craft sometimes does not register with people in this part of the world. “You know, I hear people say things — for example, in ’76, Rita recognized that the way Nigerians speak now is not the way we used to speak in the ‘60s and early ‘70s. I think it was just her and Chidi Mokeme that sounded a bit like that. I remember being in the cinema and someone was, like, ‘Why does she sound like that?’ So some people don’t know the background story and they won’t really understand. I really respected Rita because she went in and did what she felt was the truth of the character.”

Dominic and Okwo’s 17-year relationship is one of Nollywood’s interesting director-actor creative partnerships. They met in 2005, and discovered a shared belief in structure and standardizing business dealings in the industry. Okwo, a lawyer, became her manager, and they tried to put protocol in place. But certain marketers, used to direct access to top stars, disliked this, and, for a time in the 2000s, Dominic’s career was under threat. She first spoke up about this last year.

“Let me put it this way: I think they gave me a silent ban without saying anything,” she told WithChude host Chude Jideonwo. “I didn’t get work for a long time.”

Okwo had begun producing films then, and they decided to co-found their own company, The Audrey Silva Company, named after Dominic’s favourite actor Audrey Hepburn and their friend, the veteran actress Joke Silva. The Audrey Silva Company produced both The Meeting and La Femme Anjola.

Curiously, Netflix turned down The Meeting. After La Femme Anjola was pulled by FilmHouse, the two women made a major gamble and briefly made it available for paid viewership. In a Tweet announcing the decision, Okwo wrote: “For years, we have depended solely on 3rd parties to market our films. We no longer want to be paralyzed by fear every time we distribute a film which is why we have invested in coming directly to you. Let our audience determine if we are worthy.”

It was only a matter of time before a major audience had the chance, because Prime Video, setting up a welcome regional rivalry with Netflix, swooped into Nollywood and scooped up the film. Later, Magnolia Pictures picked up its North American distribution rights, placing it on streaming platforms including Apple TV, YouTube, Google Play, and Vudu.

There was a time, in the 2000s, when, as Nollywood gained bigger international recognition, the question of audience was paramount. For many industry insiders, Hollywood was the dream, crossing over. For a veteran like Dominic — who instead turned inwards to her craft and, 25 years later, is determined to thrive even as acting sets come, peak, and go — was the promise of America ever tempting?

“No,” Dominic shrugged. “For me, I want to have this body of work that anybody in the world can relate to, that any filmmaker who wants an African actress can send me the script to read for a role. I want to work anywhere in the world. I want to have a body of work that is internationally appealing. Some of the British actors, they don’t have to move to Hollywood. If there’s a role for them, their agents send the scripts. That’s what I want. I’m intentional about that.” ♦

Social media link image: Rita Dominic by Femi Alabede.

If you love what you just read, please consider making a PayPal donation to enable us to publish more like it.

More In-depth Stories in African Literature and Nigerian Film & TV

— Cover Story, December 2022: Chinelo Okparanta, Gentle Defier

— Cover Story, April 2022: The Next Generation of African Literature

— Cover Story, February 2022: The Methods of Damon Galgut

— Cover Story, September 2021: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Is in a Different Place Now

— Cover Story, July 2021: How Teju Cole Opened a New Path in African Literature

— Cover Story, January 2021: With Novels & Images, Maaza Mengiste Is Reframing Ethiopian History

— Cover Story, December 2020: How Tsitsi Dangarembga, with Her Trilogy of Zimbabwe, Overcame

— Awaiting Trial: Families of SARS Victims Speak in Devastating Documentary

— The Making of Mami Wata, Nigeria’s First Film to Premiere at Sundance

— How Dakore Egbuson and Tony Okungbowa Traverse Trauma in YE!

— Writing Omo Ghetto: The Saga, Nollywood’s Highest Grossing Film of All-Time

— Country Love Depicts Tenderness in LGBTQ Lives

One Response

Rita Dominic is a legend that loves has paid her dues in Nollywood. She is one of the standards of the industry. Kudos to her for being consistent in the industry for the past 25 years. We all should be intentional about what we want too. It will help you grow and get what you want or deserve.